"Music was my first love, and it will be my last."

John Miles’ words used to feel like a bold, teenage anthem. Now, they feel like a lifeline. I’ve aged, and the world has grown colder, but those lyrics still vibrate in my bones. Music isn't just a hobby for me; it’s my internal architecture. It’s a time machine that rips me out of the present and drops me into the lap of a memory. It’s the only thing that knows how to smile when I’m breaking, or how to weep when I’m supposed to be happy.

For years, I played it safe. I stayed within the familiar, comfortable walls of Genesis, Yes, and Oasis. I was "humanbacon" on LastFM, a digital record of a man repeating the same sounds, over and over, while his world began to quietly fracture.

By the mid-2010s, the fracture became a chasm. I was in a rut so deep it felt like a grave. My mental health wasn't just "slipping"; it was being dismantled. I felt like a ghost in my own life—useless, inadequate, a burden. The shame was so heavy that I retreated into a suffocating cocoon. I didn't just stop being social; I amputated my connections. I cut off my oldest friends because I couldn't bear for them to see the hollowed-out version of the man I used to be.

Life became a slow-motion struggle through waist-deep treacle. Every step took a year’s worth of energy. I felt stranded on the moon—stark, cold, and utterly alone—watching the Earth go about its business while I lacked the fuel to ever get home. At work, I wore a mask of confidence, but underneath, I was that proverbial duck, feet paddling in a desperate, violent blur just to keep my head above the dark water.

Then, the mask shattered.

The panic attacks didn't just happen; they hunted me. They’d strike while I was driving, forcing me to claw at the steering wheel and swerve to the shoulder, gasping for air that wouldn't come. My chest didn't just tighten; it felt like I was being fed through a mincer, rib by rib.

Recovery was a slow crawl back from the edge. But in that fragile recovery, Spotify threw me a lifeline. Amidst the prog-rock and the haunting layers of Steven Wilson’s Pariah, a name appeared: She Makes War.

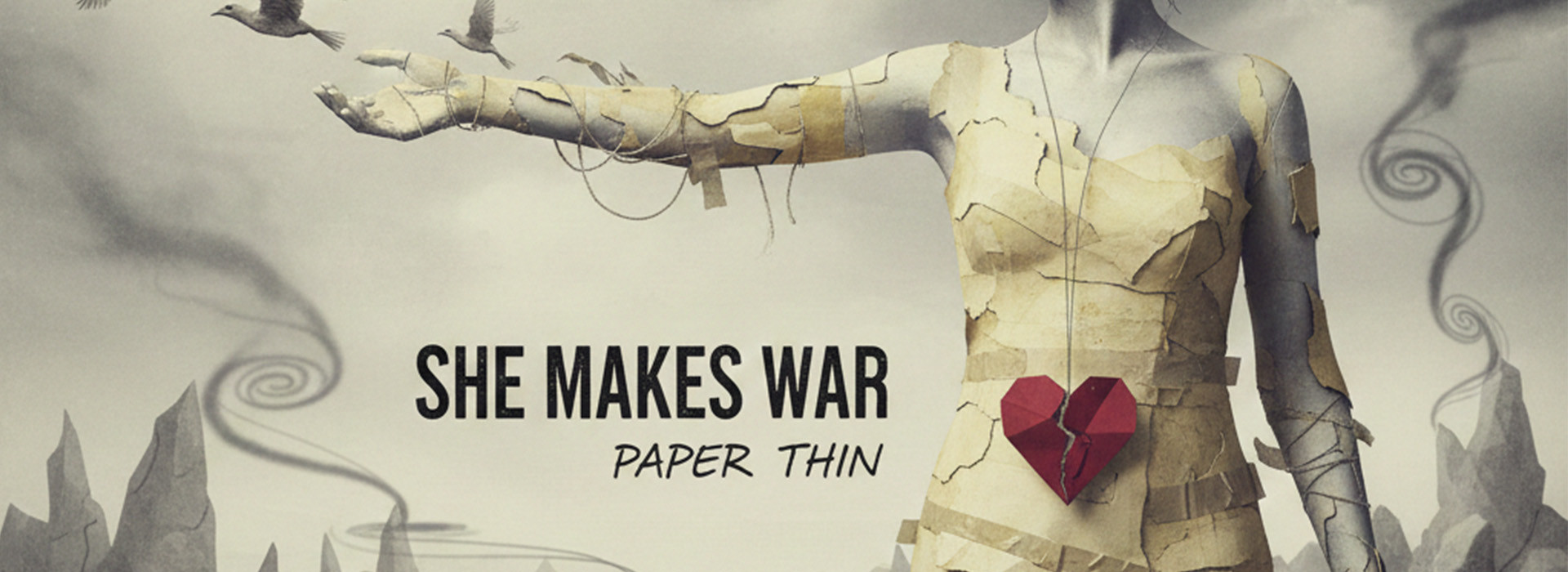

When I first heard Paper Thin, the world stopped. It didn’t just sound like a song; it sounded like a confession. It sounded like me.

"Paper Thin" was the only way to describe the membrane between me and total collapse. I felt exposed, raw, and so incredibly fragile that the mere thought of a "normal life" terrified me.

But listening to Laura Kidd, I realized I wasn't the only one shivering in this mental battleground. The song became my secret counselor. That second voice in the track felt like a hand reaching out in the dark to help me carry the weight. It was delicate, like an eggshell, yet it gave me the foundation to start rebuilding. Laura was singing my private agony back to me, and in doing so, she gave me permission to breathe again.

It’s been eight years. The road is still long, and some days the treacle is still thick. I still struggle to find my voice in a room full of people.

Last May, I finally saw Laura—now Penfriend—at a gig in Nottingham. I stood in front of her at the meet-and-greet, the words "Thank you for saving me" burning in my throat. But I stayed "paper thin." I chickened out. I managed a "hello," my old social anxieties locking the door on everything else I wanted to say.

So, if you ever read this, Laura: Thank you. Your song is on every playlist I own. On the days when the moon feels closer than the Earth, I put it on to remind myself that it’s okay to be fragile. It’s okay to be paper thin, as long as you’re still here.